Frank Miller (comics)

| Frank Miller | |

|---|---|

Miller at Comic-Con 2008 |

|

| Born | January 27, 1957 Olney, Maryland, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Area(s) | Writer Penciller Inker Film director Screenwriter Actor |

| Notable works | Batman: The Dark Knight Returns Batman: Year One Sin City Daredevil: Born Again 300 Ronin Give Me Liberty |

| Awards | Numerous |

| Official website | |

Frank Miller (born January 27, 1957)[1] is an American comic book creator and film director best known for his dark, film noir-style comic book stories and graphic novels Ronin, Daredevil: Born Again, Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, Sin City and 300. He recently directed the film version of The Spirit, shared directing duties with Robert Rodriguez on Sin City and produced the film 300.

Contents |

Personal life

Miller was born in Olney, Maryland,[2] and raised in Montpelier, Vermont,[2] the fifth of seven children of a nurse mother and a carpenter/electrician father.[3] His family was Irish Catholic.[4] Miller moved to New York City in 1976, when he was 19, to find work as a comic book artist.[5] Living in New York City's Hell's Kitchen influenced Miller's material in the 1980s. Miller lived in Los Angeles, California in the 1990s which influenced Sin City.[6] Miller moved back to Hell's Kitchen by 2001 and was creating Batman: The Dark Knight Strikes Again as the 9/11 terrorist attacks occurred.[7] In 2005 Miller divorced Lynn Varley, the award-winning colorist who had collaborated with him on several projects.

Career

Setting out to become an artist, Miller received his first published work in Gold Key Comics' licensed TV-series comic book The Twilight Zone #84 (June 1978), drawing the story "Royal Feast", and issue #85 (July 1978), drawing "Endless Cloud".[8] This was followed by penciling jobs for "Deliver Me From D-Day" short story in Weird War Tales #64 (1978), "The Greatest Story Never Told" short story, and "The Day After Doomsday" short story both in Weird War Tales #68 (1978), and "The Edge of History" short story in Unknown Soldier #219 (1978) for DC Comics and his first work for Marvel Comics, penciling the 17-page story "The Master Assassin of Mars, Part 3" in John Carter: Warlord of Mars #18 (Nov. 1978).

At Marvel, Miller would settle in as a regular fill-in and cover artist, working on a variety of titles. One of these jobs was drawing Peter Parker, the Spectacular Spider-Man #27–28 (Feb.–March 1979), which guest-starred Daredevil. At the time, sales of the Daredevil title were poor; however, Miller saw something in the character he liked and asked editor-in-chief Jim Shooter if he could work on Daredevil's regular title. Shooter agreed and made Miller the new penciller on the title. As Miller recalled in 2008,

When I first showed up in New York, I showed up with a bunch of comics, a bunch of samples, of guys in trench coats and old cars and such. And [comics editors] said, 'Where are the guys in tights?' And I had to learn how to do it. But as soon as a title came along, when [Daredevil signature artist] Gene Colan left Daredevil, I realized it was my secret in to do crime comics with a superhero in them. And so I lobbied for the title and got it".[3]

Daredevil and the early 1980s

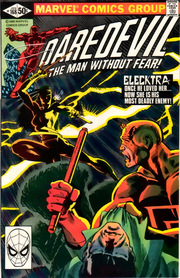

Daredevil #158 (May 1979), Miller's debut on that title, was the finale of an ongoing story written by Roger McKenzie. Although still conforming to traditional comic book styles, Miller infused this first issue with his own film noir style.[9] After this issue, Miller became one of Marvel's rising stars, and began plotting additional stories with McKenzie. Learning from Neal Adams, Miller would sit for hours sketching the roofs of New York in an attempt to give his Daredevil art an authentic feel not commonly seen in superhero comics at the time. Miller was so successful with the title that Marvel began publishing the Daredevil comic monthly (as opposed to its previous bimonthly publication period). With issue #168 (Jan. 1981), Miller took over full duties as writer and penciller, with Klaus Janson as inker. Issue #168 saw the first appearance of the ninja mercenary Elektra, who despite being an assassin-for-hire would become Daredevil's love-interest. Miller would write and draw a solo Elektra story in Bizarre Adventures #28 (Oct. 1981).

With his creation of Elektra, Miller's work on Daredevil was characterized by darker themes and stories. This peaked when in #181 (April 1982) he had the assassin Bullseye kill Elektra. Although deaths of supporting characters are common in comics, the death of a major, costumed character such as Elektra was not. Miller made it clear with the next few issues that he intended Elektra to remain dead, but nonetheless she was revived during his time as writer. Miller finished his Daredevil run with issue #191 (Feb. 1983); in his time he had transformed a second-tier character into one of Marvel's most popular.

Additionally, Miller in 1980 drew a short Batman Christmas story called "Wanted: Santa Claus-Dead or Alive" written by Denny O'Neil for DC Special Series #21. This was his first encounter with a character with which, like Daredevil, he would become closely associated.

As penciler and co-plotter, Miller, together with writer Chris Claremont, produced the miniseries Wolverine #1-4 (Sept.-Dec. 1982), inked by Josef Rubinstein and spinning off from the popular X-Men title. Miller used this miniseries to expand on Wolverine's character while featuring more manga-influenced art. The series was a critical success and further cemented Miller's place as an industry star.

His first creator-owned title was DC Comics' six-issue miniseries Ronin (1983–1984). Here Miller not only refined his own art and storytelling techniques, but also helped change how creator rights were viewed. After Ronin, Miller's only published work in 1985 was Daredevil #219, inspired by the film High Plains Drifter.

Batman: The Dark Knight Returns and the late 1980s

In 1986, DC Comics released writer-penciler Miller's Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, a four-issue miniseries printed in what the publisher called "prestige format" — squarebound, rather than stapled; on heavy-stock paper rather than newsprint, and with cardstock rather than glossy-paper covers. It was inked by Klaus Janson and colored by Lynn Varley.

The story tells how Batman retired after the death of the second Robin (Jason Todd), and at age 55 returns to fight crime in a dark and violent future. Miller created a tough, gritty portrayal of Batman, who was often referred to as the "Darknight Detective" in 1970s portrayals. Released the same year as Alan Moore's and Dave Gibbons' DC miniseries Watchmen, it showcased a new form of more adult-oriented storytelling to both comics fans and a crossover mainstream audience. The Dark Knight Returns influenced the comic-book industry by heralding a new wave of darker characters. The trade paperback collection proved to be a big seller for DC and remains in print 20 years after first being published.

By this time, Miller had returned as the writer of Daredevil. Following his self-contained story "Badlands", penciled by John Buscema, in #219 (June 1985), he co-wrote #226 (Jan. 1986) with departing writer Dennis O'Neil. Then, with artist David Mazzucchelli, he crafted a seven-issue story arc that, like The Dark Knight Returns, similarly redefined and reinvigorated its main character. The storyline, Daredevil: Born Again, in #227-233 (Feb.-Aug. 1986) chronicled the hero's Catholic background, and the destruction and rebirth of his real-life identity, Manhattan attorney Matt Murdock, at the hands of Daredevil's archnemesis, the crime lord Wilson Fisk, also known as the Kingpin.

Miller and artist Bill Sienkiewicz produced the graphic novel Daredevil: Love and War in 1986. Featuring the character of the Kingpin, it indirectly bridges Miller's first run on Daredevil and Born Again by explaining the change in the Kingpin's attitude toward Daredevil. Miller and Sienkiewicz also produced the eight-issue miniseries Elektra: Assassin for Epic Comics. Set outside regular Marvel continuity, it featured a wild tale of cyborgs and ninjas, while expanding further on Elektra's background. Both of these projects were well-received critically. Elektra: Assassin was praised for its bold storytelling, but neither it nor Daredevil: Love and War had the influence or reached as many readers as Dark Knight Returns or Born Again.

Miller's final major story in this period was in Batman issues 404-407 in 1987, another collaboration with Mazzuchelli. Titled Batman: Year One, this was Miller's version of the origin of Batman in which he retconned many details and adapted the story to fit his Dark Knight continuity. Proving to be hugely popular, this was as influential as Miller's previous work and a trade paperback released in 1988 remains in print and is one of DC's best selling books.

Miller had also drawn the covers for the first twelve issues of First Comics English language reprints of Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima's Lone Wolf and Cub. This helped bring Japanese manga to a wider Western audience.

During this time, Miller (along with Marv Wolfman, Alan Moore and Howard Chaykin) had been in dispute with DC Comics over a proposed ratings system for comics. Disagreeing with what he saw as censorship, Miller refused to do any further work for DC,[9] and he would take his future projects to the independent publisher Dark Horse Comics. From then on Miller would be a major supporter of creator rights and be a major voice against censorship in comics.

The 1990s Sin City and 300

After announcing he intended to release his work only via the independent publisher Dark Horse Comics, Miller completed one final project for Epic Comics, the mature-audience imprint of Marvel Comics. Elektra Lives Again was a fully painted graphic novel written and drawn by Miller and colored by longtime partner Lynn Varley. Telling the story of the resurrection of Elektra from the dead and Daredevil's quest to find her, it was the first example of a new style in Miller's art, as well as showing Miller's will to experiment with new story-telling techniques.

1990 saw Miller and artist Geof Darrow start work on Hard Boiled, a three-issue miniseries which suffered from long delays between issues. The title, a mix of violence and satire, was praised for Darrow's highly detailed art and Miller's writing. At the same time Miller and artist Dave Gibbons produced Give Me Liberty, a four-issue miniseries for Dark Horse. A mixture of action and political satire, the title sold well and cemented Miller's reputation as a writer of mature-audience comics. Give Me Liberty was followed by sequel miniseries and specials expanding on the story of protagonist Martha Washington, an African-American woman in modern and near-future southern North America, all of which were written by Miller and drawn by Gibbons.

Miller also wrote the scripts for the science fiction films RoboCop 2 and RoboCop 3, about a police cyborg. Neither was critically well-received. Afterward, Miller stated he would never allow Hollywood to make movie adaptations of his comics, being disgusted with what he characterized as studio interference with his scriptwriting. Miller would come into contact with the fictional cyborg once more, however, writing the comic-book minieries, RoboCop vs. The Terminator, with art by Walter Simonson. In 2003, Miller's screenplay for RoboCop 2 was adapted by Steven Grant for Avatar Press's Pulsaar imprint. Illustrated by Juan Jose Ryp, the series is called Frank Miller's RoboCop and contains plot elements that were divided between RoboCop 2 and RoboCop 3.

In 1991, Miller started work on his first Sin City story. Serialized in Dark Horse Presents #51-62, Miller wrote and drew the story in black and white to emphasize its film noir origins. Proving to be another success, the story was released in a trade paperback. This first Sin City "yarn" was rereleased in 1995 under the name The Hard Goodbye. Sin City proved to be Miller's main project for much of the remainder of the decade, as Miller told more Sin City stories within this noir world of his creation, in the process helping to revitalize the crime comics genre. Sin City proved artistically auspicious for Miller and again brought his work to a wider audience without comics.

Daredevil: Man Without Fear was a miniseries published by Marvel Comics in 1993 based on an earlier film script. In this Miller and artist John Romita Jr. told Daredevil's origins differently than in the comics. Miller also returned to superheroes by writing issue #11 of Todd McFarlane's Spawn, as well as the Spawn/Batman crossover for Image Comics.

In 1995, Miller and Darrow collaborated again on Big Guy and Rusty the Boy Robot — a homage to Godzilla movies, Astro Boy and patriotic American films from World War II. The series was published as a two-part mini-series from Dark Horse Comics. In 1999 it became an animated series on Fox Kids. During this period, Miller became one of the founding members of the comic imprint Legend, under which many of his Sin City works were released, via Dark Horse. Also, it was during the 1990s that Miller did cover art for many titles in the Comics Greatest World/Dark Horse Heroes line.

Written and illustrated by Frank Miller with painted colors by Varley, 300 was a 1998 comic-book miniseries, released as a hardcover collection in 1999, retelling of the Battle of Thermopylae and the events leading up to it from the perspective of Leonidas of Sparta. 300 was particularly inspired by the 1962 film The 300 Spartans, a movie that Miller watched as a young boy. In 2007, 300 was adapted by director Zack Snyder into a highly successful film. In 2010, Dark Horse Comics announced that Miller will write and draw a prequel to "300" titled "Xerxes" to be released sometime in 2011.

Batman: The Dark Knight Strikes Again and the 2000s

Miller started the new millennium off with the long awaited sequel to Batman: The Dark Knight Returns for DC Comics after Miller had put past difference with D.C. aside. Batman: The Dark Knight Strikes Again was initially released as a three issue series. Miller has also returned to writing Batman in 2005, taking on the writing duties of All Star Batman and Robin the Boy Wonder, a series set inside of the Earth-31 Dark Knight Universe continuity in DC's Multiverse[10] and drawn by Jim Lee. Miller has been vocally opposed to recent comic art attempting to give the cosmetic appearance of what some say is more realism. In an interview on the documentary Legends of the Dark Knight: The History of Batman, Miller said, "People are attempting to bring a superficial reality to superheroes which is rather stupid. They work best as the flamboyant fantasies they are. I mean, these are characters that are broad and big. I don't need to see sweat patches under Superman's arms. I want to see him fly."

Miller's stance against movie adaptations was to change after Robert Rodriguez made a short film from one of Miller's Sin City short stories. Rodriguez showed this short film to Miller, who was so pleased with the result that he approved a full-length film, Sin City. This would be Miller's second experience with the movie world, after becoming disenchanted years earlier with his experiences with RoboCop 2 and 3. The movie was released in the U.S. on April 1, 2005, using Miller's original comics panels as storyboards. Miller and Rodriguez are credited as codirectors, which Rodriguez insisted upon. Directors Guild of America rules permit only one person or "legitimate" directorial team (such as the Coen brothers) being listed as the director of a film. As a result, Rodriguez elected to resign from the Guild.[11] The film's success brought renewed attention to Miller and to Sin City. And the 300 film did the same for 300.

At the 2006 San Diego Comic-Con, it was announced that Miller would write and direct a film version of Will Eisner's The Spirit.[12] Upon release on December 25, 2008, The Spirit film was panned by critics and did poorly at the box office. A sequel to the film Sin City, based on the arc A Dame to Kill For, is in progress as of 2009, provisionally entitled Sin City 2.[13]

At the 2009 San Diego Comic-Con, it was revealed that Miller has finished his first draft of what will become the sequel to 300. It has been revealed on Frank's Twitter account that the sequel is in fact a prequel and will be entitled Xerxes. The story will be set 19 years before 300

At Wondercon 2010 it was announced that Miller and Jim Lee's long delayed series All Star Batman and Robin will resume publication in February 2011 and retitled Dark Knight: Boy Wonder.[14][15] Miller is currently at work on a graphic novel titled Holy Terror, about a former special ops agent ("The Fixer") taking on Al-Qaeda.[16] This title was originally conceived with Batman as the protagonist, under the title Holy Terror, Batman.[17]

Political stance

On January 24, 2007, in an interview with National Public Radio, Miller talked about his political views. On the issues of the second Iraq war and the War on Terrorism, he said:

It seems to me quite obvious that our country and the entire Western World is up against an existential force that knows exactly what it wants ... and we're behaving like a collapsing empire.

For some reason, nobody seems to be talking about who we're up against, and the sixth-century barbarism that they actually represent. These people saw people's heads off. They enslave women, they genitally mutilate their daughters, they do not behave by any cultural norms that are sensible to us. I’m speaking into a microphone that never could have been a product of their culture, and I'm living in a city where 3000 of my neighbors were killed by thieves of airplanes they never could have built.

Nobody questions why we, after Pearl Harbor, attacked Nazi Germany. It was because we were taking on a form of global fascism, we're doing the same thing now. [18][19]

Critical reaction

Initially, Miller's work was met with positive reception. The Dark Knight Returns was a great critical success and Batman: Year One was met with even greater critical praise for its gritty realism and style. However, in recent years Miller's later work has been met with criticism. Batman: The Dark Knight Strikes Again met with less positive reviews than its highly acclaimed predecessor. All Star Batman and Robin the Boy Wonder in particular has been met with harsh criticism. William Gatevackes of PopMatters said that "All Star Batman and Robin should be avoided at all costs".[20] Comics journalist Cliff Biggers of Comic Shop News called the series "one of the biggest train wrecks in comics history."[21] Iann Robinson called All Star Batman and Robin "a comic series that just spirals deeper and deeper into the abyss of unreadable", and that, "Miller has erased all the good he did for Batman with The Dark Knight Returns and Batman: Year One".[22] When All Star Batman and Robin was reprinted in the UK by Panini Comics under the Batman Legends banner, there was much criticism for how the anthology comic was marketed to children on the Irish radio talkshow Liveline with a member of the Irish Rape Crisis Centre speaking on-air, criticising the explicit content of the comic book.

Some of Miller's works have been accused of lacking humanity,[23] particularly in regard to the overabundance of prostitutes portrayed in Sin City.[24] When it was released in 2008, Miller's film adaptation of Will Eisner's The Spirit met with largely negative reviews, earning a metascore of only 30/100 at the review aggregation site Metacritic.com.[25]

Influence

His cartoonist influence includes Will Eisner, Jerry Robinson, Dick Sprang, Neal Adams, Jack Kirby, Jim Steranko, Alex Toth, Frank Frazetta, Joe Kubert, Jordi Bernet, Johnny Craig, Milton Caniff, Wally Wood, Hugo Pratt, Frank Robbins, William Gaines, José Antonio Muñoz and James Kochalka.

Miller has stated that his influence includes the writing of Mickey Spillane, Raymond Chandler, James Madison, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson.

Outside of the comic and political circuit, his influence includes art historian Kenneth Clark, and the animation by Fleischer Studios.

Cameo appearances

Frank Miller has appeared in five films in small roles, dying in each.

- In RoboCop 2 (1990), he plays "Frank, the chemist" and dies in an explosion in the drug lab.

- In Jugular Wine: A Vampire Odyssey (1994), he is killed by vampires in front of Marvel Comics' Stan Lee, who compares his killers to "angels".

- In Daredevil (2003), he appears as a corpse with a pen in his head, thrown by Bullseye, who steals his motorcycle. The credits list Frank Miller as "Man with Pen in Head".

- In Sin City (2005), he plays the priest killed by Marv in the confessional.

- In The Spirit (2008), which was written and directed by Miller, he appears as "Liebowitz", the officer whose head is ripped off by the Octopus and thrown at the Spirit. The name alludes to Jack Liebowitz, a co-founder of what would become DC Comics.[26]

Frank Miller also appeared in an episode of the television series Moonlighting as a customer at a box office.

Bibliography

Comics

DC Comics

- All-Star Batman and Robin the Boy Wonder #1-10 (writer, with art by Jim Lee, 2005–08)

- Batman #404-407 (writer, with art by David Mazzucchelli, 1987)

- Batman: The Dark Knight Returns #1-4 (miniseries) (writer/artist, 1986)

- Batman: The Dark Knight Strikes Again #1-3 (miniseries) (writer/artist, 2001)

- Holy Terror, Batman! (has been cancelled) (graphic novel)

- DC Special Series #21 (artist, with writer Denny O'Neil, 1979)

- Orion #3 (artist, with writer Walt Simonson, 2000)

- Ronin #1-6 (miniseries) (writer/artist, 1983)

- Spawn/Batman (writer, with art by Todd McFarlane, 1994)

- Superman #400 (artist, 1984)

- Superman: The Secret Years #1-4 (covers, 1985)

- Unknown Soldier #219 (artist, 1978)

- Weird War Tales #64, 68 (artist, 1978)

- Wonder Woman #298 (cover, 1982)

Marvel Comics

- Amazing Spider-Man Annual #14-15 (artist, with writer Denny O'Neil, 1980–81); #203, 218-219 (covers, 1980–81)

- Bizarre Adventures #28 (Elektra) (writer/artist, 1981), #31 (artist, 1982)

- Daredevil #158-161, 163-167 (artist, 1979–1980); #168–184, 191 (writer/artist, 1981–83); #185-190 (writer, with art by Klaus Janson, 1982–83); #219 (writer, with art by John Buscema, 1985); #226-233 (writer, with art by David Mazzucchelli, 1985–1986)

- Daredevil: Love and War (writer, with art by Bill Sienkiewicz, 1986) (graphic novel ISBN 0-87135-172-2)

- Daredevil: The Man Without Fear #1-5 (miniseries) (writer, with art by John Romita, Jr., 1993)

- Elektra: Assassin #1-8 (miniseries) (writer, with art by Bill Sienkiewicz, 1986)

- Elektra Lives Again (graphic novel ISBN 0-7851-0890-4) (writer/artist, 1990)

- Incredible Hulk Annual #11 (artist, with writer Mary Jo Duffy, 1981)

- John Carter, Warlord of Mars #18 (artist, with writer Chris Claremont, 1978)

- Marvel Fanfare #18 (Captain America) (writer/artist, 1984)

- Marvel Spotlight (vol. 2) #8 (artist, with writer Mike W. Barr, 1980)

- Marvel Team-Up #100 (artist, with writer Chris Claremont, 1980), Annual #4 (writer, art by Herb Trimpe, 1981); #95, 99-100, 102, 106 (covers, 1980–81)

- Marvel Two-in-One #51 (artist, with writer Peter Gillis, 1979)

- Power Man and Iron Fist #76 (1981) (artist, with writers Chris Claremont and Mike W. Barr, 1981)

- Spectacular Spider-Man #27–28 (artist, with writer Bill Mantlo, 1979); #46, 48, 50-52, 54-57, 60 (covers, 1980–81)

- Spider-Man and Daredevil Special Edition (cover, 1984)

- Star Trek #5, #10 (covers)

- What If? #28, 34-35 (writer/artist, 1981–82)

- Wolverine #1-4 miniseries (artist, with writer Chris Claremont, 1982)

Dark Horse

- A Decade of Dark Horse #1 "Daddy´s Little Girl" story (writer/artist, 1993)

- Autobiografix one-shot (writer/artist among other authors, 2003) (tpb ISBN 1-59307-038-1)

- Dark Horse Maverick 2000 one-shot (writer/artist among other authors, 2000)

- Dark Horse Maverick: Happy Endings one-shot (writer/artist among other authors, 2002) (trade paperback ISBN 1-56971-820-2)

- Dark Horse 5th Anniversary (writer/artist)

- Dark Horse Presents #51-62 (writer/artist, 1991–92)

- Give Me Liberty #1-4 (writer, with art by Dave Gibbons, 1990)

- Hard Boiled #1-3 (writer, with art by Geof Darrow, 1990–92) (also trade paperback ISBN 1-878574-58-2)

- Madman #6-7 (writer, 1995)

- RoboCop vs. The Terminator #1-4 (writer, with art by Walter Simonson, 1992)

- Sin City (writer/artist) includes:

- A Dame to Kill For #1-6 (1994) (also trade paperback ISBN 1-59307-294-5)

- The Big Fat Kill #1-5 (1994) (also trade paperback ISBN 1-59307-295-3)

- That Yellow Bastard #1-6 (1996) (also trade paperback ISBN 1-59307-296-1)

- Family Values (1997) (graphic novel ISBN 1-59307-297-X)

- Booze, Broads, & Bullets (1998) (trade paperback ISBN 1-59307-298-8) collects:

- The Babe Wore Red (And Other Stories) (1994)

- Silent Night (1994)

- Lost, Lonely, & Lethal (1996)

- Sex & Violence (1997)

- Just Another Saturday Night (1997)

- Hell and Back #1-9 (1999) (also trade paperback ISBN 1-59307-299-6)

- The Big Guy and Rusty the Boy Robot #1-2 (writer, with art by Geof Darrow, 1995) (also trade paperback ISBN 1-56971-201-8)

- 300 #1-5 (writer/artist, 1998) (also hardcover ISBN 1-56971-402-9)

Valiant Comics

Miller drew the covers for all the August 1992 dated Valiant Comics as part of the Unity crossover:

- Archer & Armstrong #1 (cover)

- Eternal Warrior #1 (cover)

- Harbinger #8 (cover)

- Magnus, Robot Fighter #15 (cover)

- Rai #6 (cover)

- Shadowman #4 (cover)

- Solar, Man of the Atom #12 (cover)

- X-O Manowar #7 (cover)

Other publishers

- Bone #38 (cover, 2000)

- Destroyer Duck #7 (cover) (Eclipse Comics)

- Spawn #11 (writer) (Image Comics)

- Twilight Zone #84-85 (artist) (Gold Key Comics) 1978

- Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow (cover) [27]

Compilations

- Batman: Year One ISBN 0-930289-33-1

- Batman: The Dark Knight Returns tpb ISBN 1-56389-342-8)

- Batman: The Dark Knight Strikes Again tpb ISBN 1-56389-929-9)

- Complete Frank Miller Spider-Man (includes PPTSSM #27-28, ASM Annual #14–15, MTU #100, Annual #4 and all his covers for MTU, PPTSSM and ASM) (trade paperback ISBN 0-7851-0899-8)

- Daredevil: Born Again (collects Daredevil #227–233 (1985–86) ISBN 0-87135-297-4)

- Daredevil: The Man Without Fear tpb ISBN 0-7851-0046-6)

- Daredevil Visionaries – Frank Miller Vol.1 tpb (collects Daredevil #158–161, #163–167)

- Daredevil Visionaries – Frank Miller Vol.2 tpb (collects Daredevil #168–182) ISBN 0-7851-0771-1

- Daredevil Visionaries – Frank Miller Vol.3 tpb (collects Daredevil #183–191, What If...? #28, 35, Bizarre Adventures #28) ISBN 0-7851-0802-5

- Elektra: Assassin tpb ISBN 0-87135-309-1)

- Spawn/Batman ISBN 1-58240-019-9

- Sin City: The Hard Goodbye (1991) (collects Dark Horse Presents #51-62 and Dark Horse Presents Fifth Anniversary #1) (also trade paperback featuring the full version, ISBN 1-59307-293-7)

- The Life and Times of Martha Washington in The Twenty-First Century (writer, with art by Dave Gibbons, Dark Horse Comics, hardcover, 600 pages, July 2009, ISBN 1-59307-654-1) collects:

- Give Me Liberty #1-4 (mini-series, 1990, tpb, ISBN 0-440-50446-5)

- Martha Washington Goes to War #1-5 (mini-series, 1994, tpb, ISBN 1-56971-090-2)

- Happy Birthday, Martha Washington (one-shot, 1995)

- Martha Washington Stranded in Space (one-shot, 1995) (features The Big Guy)

- Martha Washington Saves the World (3-issue mini-series, 1997, tpb ISBN 1-56971-384-7)

- Martha Washington Dies (one-shot, 2007)

- Tales to Offend #1 (1997) (collects two Lance Blastoff stories and "Sin City: Daddy's Little Girl")

Movies

- RoboCop 2 Miller's original script was heavily edited through rewrites as it was deemed unfilmable. The original script was adapted in 2003 by Steven Grant into the comics series, Frank Miller's RoboCop.

- RoboCop 3 Miller co-wrote this with the film's director Fred Dekker.

- Batman: Year One This was co-written and was due to be directed by Darren Aronofsky until Warner Bros. cancelled the project opting for Christopher Nolan's Batman Begins.

- Sin City

- The Spirit Although Miller co-directed Sin City this is his first solo directing project.

- Sin City 2 Miller confirmed along with Robert Rodriguez that they will be working on a sequel to Sin City at a 2007 comic-con.

Miller was a producer for the film 300, which was adapted shot for shot into a feature film in 2007. The 2003 film version of Daredevil predominantly use the tone and stories written and established by Frank Miller. Miller did not have any direct creative input into Daredevil.

Awards

Eisner Awards

- Best Short Story - 1995 "The Babe Wore Red", in Sin City: The Babe Wore Red and Other Stories (Dark Horse/Legend)

- Best Finite Series/Limited Series - 1991 Give Me Liberty (Dark Horse), 1995 Sin City: A Dame to Kill For (Dark Horse/Legend), 1996 Sin City: The Big Fat Kill (Dark Horse/Legend), 1999 300 (Dark Horse)

- Best Graphic Album: New - 1991 Elektra Lives Again (Marvel)

- Best Graphic Album: Reprint - 1993 Sin City (Dark Horse), 1998 Sin City: That Yellow Bastard (Dark Horse)

- Best Writer/Artist - 1991 for Elektra Lives Again (Marvel), 1993 for Sin City (Dark Horse), 1999 for 300 (Dark Horse)

- Best Artist/Penciller/Inker or Penciller/Inker Team - 1993 for Sin City (Dark Horse)

Kirby Awards

- Best Single Issue - 1986 Daredevil #227 "Apocalypse" (Marvel), 1987 Batman: The Dark Knight Returns #1 "The Dark Knight Returns" (DC)

- Best Graphic Album, 1987 Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (DC)

- Best Writer/Artist (single or team) - 1986 Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli, for Daredevil: Born Again (Marvel)

- Best Art Team - 1987 Frank Miller, Klaus Janson and Lynn Varley, for Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (DC)

Harvey Awards

- Best Continuing or Limited Series - 1996 Sin City (Dark Horse), 1999 300 (Dark Horse)

- Best Graphic Album of Original Work - 1998 Sin City: Family Values (Dark Horse)

- Best Domestic Reprint Project - 1997 Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, 10th Anniversary Edition (DC)

- Palme d'Or - 2005 (nominated) Sin City (Dimension Films)

Scream Awards

- The Comic-Con Icon Award - 2006

References

- ↑ Comics Buyer's Guide #1650; February 2009; Page 107

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Andy Webster (July 20, 2008). "Artist-Director Seeks the Spirit of 'The Spirit'". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/20/movies/20webs.html.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Frank Lovece (December 22, 2008). "Spirit guide: Frank Miller adapts Will Eisner's cult comic". FilmJournal.com. http://www.filmjournal.com/filmjournal/content_display/esearch/e3i8a7ba6d185c56a44dde220cb5168caff.

- ↑ Applebaum, Stephen (22 December 2008). "Frank Miller interview: It's no sin". The Scotsman (Edinburgh). http://thescotsman.scotsman.com/features/Frank-Miller-interview-It39s-no.4812742.jp. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ↑ [1], IMDb

- ↑ Matt Brady. FRANK MILLER SPOTLIGHT PANEL, PART 1, Newsarama, February 20, 2006

- ↑ David Brothers. Sons of DKR: Frank Miller x TCJ, 4thletter, April 6, 2009

- ↑ "The Complete Frank Miller: The Twilight Zone". http://moebiusgraphics.com/comics/twilightzone.php.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Flinn, Tom. "Writer's Spotlight: Frank Miller: Comics' Noir Auteur," ICv2: Guide to Graphic Novels #40 (Q1 2007).

- ↑ "A QUICK MILLER MINUTE ON ALL-STAR BATMAN AND ROBIN", Cliff Biggers Newsarama, February 9, 2005

- ↑ Brian Ashcraft (April, 2005). "The Man Who Shot Sin City". Wired News. http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/13.04/sincity.html.

- ↑ ""Spirit" comic comes to life on big screen". yahoo.com. July 19, 2006. http://movies.yahoo.com/mv/news/va/20060719/115331503300.html.

- ↑ Shawn Adler (May 26, 2007). "Depp, Banderas To Call 'Sin City' Home?". MTV News. http://www.mtv.com/news/articles/1555630/20070326/story.jhtml.

- ↑ http://dcu.blog.dccomics.com/2010/04/02/whats-next-for-frank-miller-and-jim-lee/#comments

- ↑ http://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=article&id=25536

- ↑ Sean O'Neal (July 30, 2010). "Frank Miller scraps his "Batman vs. Al Qaeda story". The A.V. Club. http://www.avclub.com/articles/frank-miller-scraps-his-batman-vs-alqaeda-story,43662/.

- ↑ Frank Lovece (December 21, 2008). "Fast Chat: Frank Miller". Newsday. http://www.newsday.com/services/newspaper/printedition/sunday/fanfare/ny-fffast5968802dec21,0,7134105.story.

- ↑ "Writers, Artists Describe State of the Union". Talk of the Nation (NPR). January 24, 2007. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=7002481.

- ↑ Joshua Zader (March 10, 2007). "NPR Interview with 300’s Frank Miller". The Atlasphere. http://www.theatlasphere.com/metablog/612.php.

- ↑ William Gatevackes (February 10, 2006). "ALL-STAR BATMAN & ROBIN #1-3". PopMatters. http://www.popmatters.com/comics/all-star-batman-robin-1-3.shtml.

- ↑ Comic Shop News #1064 November 7, 2007

- ↑ Iann Robinson. "Review". Crave Online. http://www.craveonline.com/articles/comics/04649326/all_star_batman_and_robin.html.

- ↑ A. O. Scott (April 24, 2005). "The Unreal Road From Toontown to 'Sin City'". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/24/movies/24scot.html?ex=1271995200&en=83f36c443f1c41eb&ei=5088&partner=rssnyt&emc=rss.

- ↑ Manohla Dargis (April 1, 2005). "A Savage and Sexy City of Pulp Fiction Regulars". New York Times. http://movies.nytimes.com/2005/04/01/movies/01sin.html?_r=1&ex=1153281600&en=7e266ef33d532f3a&ei=5070&oref=slogin.

- ↑ [2], Metacritic.com

- ↑ Lovece, FilmJournal.com sidebar: "The Annotated Spirit: A Guide to the Movie's In-joke References"

- ↑ Amazon.com: Gravity's Rainbow (Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition): Thomas Pynchon, Frank Miller: Books

External links

- Official website

- Frank Miller at the Comic Book DB

- The Complete Works of Frank Miller

- Frank Miller at the Internet Movie Database

- Frank Miller at the Open Directory Project

| Preceded by Jim Shooter |

Daredevil writer 1980 (with Roger McKenzie) |

Succeeded by N/A |

| Preceded by Roger McKenzie |

Daredevil writer 1981–1983 |

Succeeded by Dennis O'Neil |

| Preceded by Gene Colan |

Daredevil artist 1979–1982 |

Succeeded by Klaus Janson |

| Preceded by Dennis O'Neil |

Daredevil writer 1986 |

Succeeded by Ann Nocenti |

|

||||||||||||||||||||